Difference between revisions of "Madder"

| (10 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[File:Madderdress64676.jpg|thumb| Womens dress MFA# 64.676]] | + | [[File:Madderdress64676.jpg|thumb| Womens dress <br>MFA# 64.676]] |

| + | == Description == | ||

[[File:rubiatintoriaPD1.jpg|thumb|Madder plant ''Rubia tinctorum'' L.]] | [[File:rubiatintoriaPD1.jpg|thumb|Madder plant ''Rubia tinctorum'' L.]] | ||

| − | + | [[File:madder_root_1.jpg|thumb|Madder root (''Rubia tinctorum'')]] | |

| − | |||

A natural red dye extracted from the roots of any of several species of the genus ''Rubia''. The most commonly used plants include: ''Rubia tinctorum'' L., native to the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, but cultivated across Europe and introduced into the Far East, America, and Africa; ''Rubia cordifolia'' L., native to India and southeast Asia, but very widespread; and ''Rubia akane'' Nagai, found in Japan and also China, Korea and Taiwan. Madder has been used as a colorant for dyeing textiles since ancient times in India, Persia, and Egypt. Its cultivation and use then spread across the Mediterranean regions and into Europe: it was well known in Classical Greek and Roman times as both a dye and a pigment. Its use continued in Europe thereafter, notably for dyeing [[wool]]. From the 13th century it was cultivated in France, parts of Spain, northern Italy and notably the Netherlands (Zeeland) and was of great economic importance. The dye was also used for lake pigment preparation, but in 15th–17th-century Europe it was commonly obtained from dyed textile (usually wool), rather than from the root directly. The lengthy and complicated method of dyeing the vivid red colour on [[cotton]] known as [[Turkey red]], first seen in Europe on printed cottons imported from India in the 17th century, only became known in western Europe in the second half of the 18th century, but the color quickly became extremely popular and the cultivation and use of madder became an important industry, particularly in France. During the first half of the 19th century, research was carried out to isolate and identify the constituents of the dye, and also to improve the yield of dye from the root. The most important constituents are [[alizarin, natural|alizarin]] (red) and [[pseudopurpurin]] from which [[purpurin]] (red) is formed by decarboxylation (or, in treated roots, acid hydrolysis); other constituents present in the fresh or dried root include [[rubiadin]], [[munjistin]], lucidin, [[xanthopurpurin]], and others. Alizarin and pseudopurpurin are present in the root as glycosides (sugars) and treatments with acid or by fermentation were devised to hydrolyse these sugars to increase the quantity of free alizarin and purpurin available. The derivatives produced included [[garancine]] and fleurs de garance (flowers of madder). Kopp’s purpurin, widely used in the latter part of the 19th century for making madder lakes, was prepared by extracting madder root with [[sulfurous acid|sulfurous]] and [[sulfuric acid|sulfuric acids]]; it contains largely pseudopurpurin and purpurin. The dye is extracted from the dried, powdered root when it is heated in water, but the dyestuff composition is affected by temperature and the extent to which the sugars have been broken down; many dyeing and pigment-making procedures are carried out at quite low temperatures. Aluminum lakes of dye extracted from the madder root or from a madder derivative were popular artists' pigments in the 19th century: for example [[rose madder]] were used as artists pigments. Madder forms a bright red color when precipitated on an amorphous hydrated alumina substrate, such as [[alumina trihydrate]]. Tin, chromium, and iron mordants can produce purple, brown, and pink colors, respectively. After commercial introduction of the [[alizarin, synthetic|synthetic alizarin]] in 1871, the use of the natural product for textile dyes declined rapidly, though natural rose madder was, and still is, used as a lake for artists' colors. The presence of pseudopurpurin along with alizarin has been used to distinguish natural madder dyes from the synthetic alizarin dyes. Pseudopurpurin and purpurin fluoresce a bright yellow-orange while alizarin produces a pale violet color. | A natural red dye extracted from the roots of any of several species of the genus ''Rubia''. The most commonly used plants include: ''Rubia tinctorum'' L., native to the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, but cultivated across Europe and introduced into the Far East, America, and Africa; ''Rubia cordifolia'' L., native to India and southeast Asia, but very widespread; and ''Rubia akane'' Nagai, found in Japan and also China, Korea and Taiwan. Madder has been used as a colorant for dyeing textiles since ancient times in India, Persia, and Egypt. Its cultivation and use then spread across the Mediterranean regions and into Europe: it was well known in Classical Greek and Roman times as both a dye and a pigment. Its use continued in Europe thereafter, notably for dyeing [[wool]]. From the 13th century it was cultivated in France, parts of Spain, northern Italy and notably the Netherlands (Zeeland) and was of great economic importance. The dye was also used for lake pigment preparation, but in 15th–17th-century Europe it was commonly obtained from dyed textile (usually wool), rather than from the root directly. The lengthy and complicated method of dyeing the vivid red colour on [[cotton]] known as [[Turkey red]], first seen in Europe on printed cottons imported from India in the 17th century, only became known in western Europe in the second half of the 18th century, but the color quickly became extremely popular and the cultivation and use of madder became an important industry, particularly in France. During the first half of the 19th century, research was carried out to isolate and identify the constituents of the dye, and also to improve the yield of dye from the root. The most important constituents are [[alizarin, natural|alizarin]] (red) and [[pseudopurpurin]] from which [[purpurin]] (red) is formed by decarboxylation (or, in treated roots, acid hydrolysis); other constituents present in the fresh or dried root include [[rubiadin]], [[munjistin]], lucidin, [[xanthopurpurin]], and others. Alizarin and pseudopurpurin are present in the root as glycosides (sugars) and treatments with acid or by fermentation were devised to hydrolyse these sugars to increase the quantity of free alizarin and purpurin available. The derivatives produced included [[garancine]] and fleurs de garance (flowers of madder). Kopp’s purpurin, widely used in the latter part of the 19th century for making madder lakes, was prepared by extracting madder root with [[sulfurous acid|sulfurous]] and [[sulfuric acid|sulfuric acids]]; it contains largely pseudopurpurin and purpurin. The dye is extracted from the dried, powdered root when it is heated in water, but the dyestuff composition is affected by temperature and the extent to which the sugars have been broken down; many dyeing and pigment-making procedures are carried out at quite low temperatures. Aluminum lakes of dye extracted from the madder root or from a madder derivative were popular artists' pigments in the 19th century: for example [[rose madder]] were used as artists pigments. Madder forms a bright red color when precipitated on an amorphous hydrated alumina substrate, such as [[alumina trihydrate]]. Tin, chromium, and iron mordants can produce purple, brown, and pink colors, respectively. After commercial introduction of the [[alizarin, synthetic|synthetic alizarin]] in 1871, the use of the natural product for textile dyes declined rapidly, though natural rose madder was, and still is, used as a lake for artists' colors. The presence of pseudopurpurin along with alizarin has been used to distinguish natural madder dyes from the synthetic alizarin dyes. Pseudopurpurin and purpurin fluoresce a bright yellow-orange while alizarin produces a pale violet color. | ||

| − | [[ | + | * See also [[https://cameo.mfa.org/wiki/Category:Uemura_dye_archive '''Uemera Dye Archive''' (Akane)]] and [[https://cameo.mfa.org/wiki/Category:Natural_Dyes '''Dye Analysis''' (Madder)]] |

[[File:02 akane_madder.jpg|thumb|''Akane'']] | [[File:02 akane_madder.jpg|thumb|''Akane'']] | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

''Rubia tinctorum;'' Pigment Red 83; CI 58000:1; Natural Red 9; CI Nos. 75330, 75420; alizarin (natural); purpurin (natural); xanthine (natural); Färberröte (Deut.); Krapplack (Deut.); Krapp (Deut.); garance (Fr.); laca de rubia (Esp.); granza (Esp.); robbia (It.); garanza (It.); rizari (Gr.); meekrap (Ned.); garança (Port.); rose madder; Turkey red; garancine; dyer's root; madder lake; alizarin red | ''Rubia tinctorum;'' Pigment Red 83; CI 58000:1; Natural Red 9; CI Nos. 75330, 75420; alizarin (natural); purpurin (natural); xanthine (natural); Färberröte (Deut.); Krapplack (Deut.); Krapp (Deut.); garance (Fr.); laca de rubia (Esp.); granza (Esp.); robbia (It.); garanza (It.); rizari (Gr.); meekrap (Ned.); garança (Port.); rose madder; Turkey red; garancine; dyer's root; madder lake; alizarin red | ||

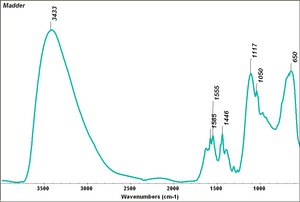

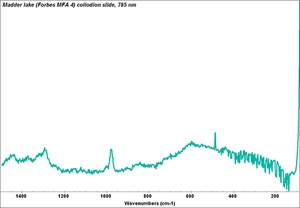

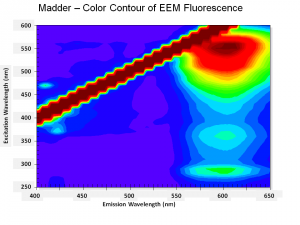

| − | [[[SliderGallery rightalign|Madder.TIF~FTIR (MFA)|Madder lake (Forbes MFA 4) collodion slide, 785 nm resize.tif | + | [[[SliderGallery rightalign|Madder.TIF~FTIR (MFA)|Madder lake (Forbes MFA 4) collodion slide, 785 nm resize.tif~Raman (MFA)|Madder color.PNG~EEM color (MFA)|Madder line.PNG~EEM line (MFA)]]] |

| + | == Risks == | ||

| + | |||

| + | May cause some allergic reactions. May discolor with alkaline treatments | ||

| − | == | + | == Physical and Chemical Properties == |

Purpurin fluoresces a bright yellow-orange while alizarin produces a pale violet color. | Purpurin fluoresces a bright yellow-orange while alizarin produces a pale violet color. | ||

ASTM (1999) lightfastness = IV (poor) | ASTM (1999) lightfastness = IV (poor) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Additional Images == | == Additional Images == | ||

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

| − | |||

File:madder_powder_2.jpg|Madder powder (''Rubia tinctorum'') | File:madder_powder_2.jpg|Madder powder (''Rubia tinctorum'') | ||

File:3839 Madder_3up.jpg|Madder, Madder root, and Madder seed | File:3839 Madder_3up.jpg|Madder, Madder root, and Madder seed | ||

| Line 46: | Line 38: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| + | == Resources and Citations == | ||

| + | |||

| + | * H. Schweppe, Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe: Vorkommen, Verwendung, Nachweis, Ecomed, Landsberg/Lech, 1993 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Pigments Through the Ages: [http://webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/alizarin.html Madder Lake]Record content reviewed by EU-Artech, November 2007 | ||

| − | + | * Analytical strategies for natural dyestuffs in cultural heritage objects - EU-ARTECH European research project - http://www.organic-colorants.org | |

| − | * | + | * Jo Kirby, Submitted information, November 2007 |

* H. Schweppe, ''Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe: Vorkommen, Verwendung, Nachweis'', Ecomed, Landsberg/Lech, 1993 | * H. Schweppe, ''Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe: Vorkommen, Verwendung, Nachweis'', Ecomed, Landsberg/Lech, 1993 | ||

| Line 63: | Line 60: | ||

* J. Kirby, M. Spring, and C.Higgitt, "The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate", ''National Gallery Technical Bulletin'', 26, 71-85, 2005 | * J. Kirby, M. Spring, and C.Higgitt, "The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate", ''National Gallery Technical Bulletin'', 26, 71-85, 2005 | ||

| − | * ''Encyclopedia Britannica'', http://www.britannica.com Comment: Madder. Retrieved June 5, 2003 | + | * ''Encyclopedia Britannica'', http://www.britannica.com Comment: Madder. Retrieved June 5, 2003. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

* ''Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics'', Elisabeth West FitzHugh, Oxford University Press, Oxford, Vol. 3, 1997 Comment: H.Schweppe, J.Winter, "Madder and Alizarin" | * ''Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics'', Elisabeth West FitzHugh, Oxford University Press, Oxford, Vol. 3, 1997 Comment: H.Schweppe, J.Winter, "Madder and Alizarin" | ||

Latest revision as of 12:18, 22 June 2022

Description

A natural red dye extracted from the roots of any of several species of the genus Rubia. The most commonly used plants include: Rubia tinctorum L., native to the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, but cultivated across Europe and introduced into the Far East, America, and Africa; Rubia cordifolia L., native to India and southeast Asia, but very widespread; and Rubia akane Nagai, found in Japan and also China, Korea and Taiwan. Madder has been used as a colorant for dyeing textiles since ancient times in India, Persia, and Egypt. Its cultivation and use then spread across the Mediterranean regions and into Europe: it was well known in Classical Greek and Roman times as both a dye and a pigment. Its use continued in Europe thereafter, notably for dyeing Wool. From the 13th century it was cultivated in France, parts of Spain, northern Italy and notably the Netherlands (Zeeland) and was of great economic importance. The dye was also used for lake pigment preparation, but in 15th–17th-century Europe it was commonly obtained from dyed textile (usually wool), rather than from the root directly. The lengthy and complicated method of dyeing the vivid red colour on Cotton known as Turkey red, first seen in Europe on printed cottons imported from India in the 17th century, only became known in western Europe in the second half of the 18th century, but the color quickly became extremely popular and the cultivation and use of madder became an important industry, particularly in France. During the first half of the 19th century, research was carried out to isolate and identify the constituents of the dye, and also to improve the yield of dye from the root. The most important constituents are alizarin (red) and Pseudopurpurin from which Purpurin (red) is formed by decarboxylation (or, in treated roots, acid hydrolysis); other constituents present in the fresh or dried root include Rubiadin, Munjistin, lucidin, Xanthopurpurin, and others. Alizarin and pseudopurpurin are present in the root as glycosides (sugars) and treatments with acid or by fermentation were devised to hydrolyse these sugars to increase the quantity of free alizarin and purpurin available. The derivatives produced included Garancine and fleurs de garance (flowers of madder). Kopp’s purpurin, widely used in the latter part of the 19th century for making madder lakes, was prepared by extracting madder root with sulfurous and sulfuric acids; it contains largely pseudopurpurin and purpurin. The dye is extracted from the dried, powdered root when it is heated in water, but the dyestuff composition is affected by temperature and the extent to which the sugars have been broken down; many dyeing and pigment-making procedures are carried out at quite low temperatures. Aluminum lakes of dye extracted from the madder root or from a madder derivative were popular artists' pigments in the 19th century: for example Rose madder were used as artists pigments. Madder forms a bright red color when precipitated on an amorphous hydrated alumina substrate, such as Alumina trihydrate. Tin, chromium, and iron mordants can produce purple, brown, and pink colors, respectively. After commercial introduction of the synthetic alizarin in 1871, the use of the natural product for textile dyes declined rapidly, though natural rose madder was, and still is, used as a lake for artists' colors. The presence of pseudopurpurin along with alizarin has been used to distinguish natural madder dyes from the synthetic alizarin dyes. Pseudopurpurin and purpurin fluoresce a bright yellow-orange while alizarin produces a pale violet color.

- See also [Uemera Dye Archive (Akane)] and [Dye Analysis (Madder)]

Synonyms and Related Terms

Rubia tinctorum; Pigment Red 83; CI 58000:1; Natural Red 9; CI Nos. 75330, 75420; alizarin (natural); purpurin (natural); xanthine (natural); Färberröte (Deut.); Krapplack (Deut.); Krapp (Deut.); garance (Fr.); laca de rubia (Esp.); granza (Esp.); robbia (It.); garanza (It.); rizari (Gr.); meekrap (Ned.); garança (Port.); rose madder; Turkey red; garancine; dyer's root; madder lake; alizarin red

Risks

May cause some allergic reactions. May discolor with alkaline treatments

Physical and Chemical Properties

Purpurin fluoresces a bright yellow-orange while alizarin produces a pale violet color.

ASTM (1999) lightfastness = IV (poor)

Additional Images

Resources and Citations

- H. Schweppe, Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe: Vorkommen, Verwendung, Nachweis, Ecomed, Landsberg/Lech, 1993

- Pigments Through the Ages: Madder LakeRecord content reviewed by EU-Artech, November 2007

- Analytical strategies for natural dyestuffs in cultural heritage objects - EU-ARTECH European research project - http://www.organic-colorants.org

- Jo Kirby, Submitted information, November 2007

- H. Schweppe, Handbuch der Naturfarbstoffe: Vorkommen, Verwendung, Nachweis, Ecomed, Landsberg/Lech, 1993

- D. Cardon, Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science (original edition Le Monde des teintures naturelles), Archetype Publications, Ltd., London, 2007

- R. Chenciner, Madder Red: A History of Luxury and Trade, Curson Press, Richmond (Surrey), 2000

- J.H. Hofenk de Graaff, The Colourful Past: Origins, Chemistry, and identification of Natural Dyestuffs, Archetype Publications, Ltd., London, Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg;, 2004

- J. Kirby, M. Spring, and C. Higgitt, "The Technology of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Red Lake Pigments", National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 28, 69-95, 2007

- J. Kirby, M. Spring, and C.Higgitt, "The Technology of Red Lake Pigment Manufacture: Study of the Dyestuff Substrate", National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 26, 71-85, 2005

- Encyclopedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com Comment: Madder. Retrieved June 5, 2003.

- Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, Elisabeth West FitzHugh, Oxford University Press, Oxford, Vol. 3, 1997 Comment: H.Schweppe, J.Winter, "Madder and Alizarin"

- R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia, Dover Publications, New York, 1966 Comment: p. 126

- Ralph Mayer, A Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques, Harper and Row Publishers, New York, 1969 (also 1945 printing)

- Judith Hofenk-de Graaff, Natural Dyestuffs: Origin, Chemical Constitution, Identification, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam, 1969

- Reed Kay, The Painter's Guide To Studio Methods and Materials, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1983

- Palmy Weigle, Ancient Dyes for Modern Weavers, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York, 1974

- Michael McCann, Artist Beware, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York City, 1979

- R.D. Harley, Artists' Pigments c. 1600-1835, Butterworth Scientific, London, 1982

- Matt Roberts, Don Etherington, Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books: a Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1982

- Thomas B. Brill, Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities, Plenum Press, New York City, 1980

- F. Crace-Calvert, Dyeing and Calico Printing, Palmer & Howe, London, 1876

- J. Thornton, 'The Use of Dyes and Colored Varnishes in Wood Polychromy', Painted Wood: History and Conservation, The Getty Conservation Insitute, Los Angeles, 1998

- Book and Paper Group, Paper Conservation Catalog, AIC, 1984, 1989

- Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabulary/aat/, J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles, 2000