Difference between revisions of "Anatase"

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

| − | + | Anatase, [[rutile]] and [[brookite]] are three naturally occurring isomorphic forms of [[titanium%20dioxide|titanium dioxide]]. Anatase forms translucent or transparent crystals (octahedrite) varying in color from black to reddish brown, yellowish brown, dark blue or gray. Deposits have been found in the Alps, Brazil, and the Ural Mountains; it is also formed by the weathering of titanite (sphene) and ilmenite. Mineral anatase is not a major component of artists' materials; however, it has been reported as a minor constituent (<2%) in white paints on ancient artifacts from diverse sites, as a mineral impurity in white clay-based pigments. | |

| − | Anatase was produced synthetically in the early 20th century for use as a white paint pigment with remarkable hiding power. The most successful processes were based on extraction from crushed and roasted ilmenite (iron titanate). The major problems in producing a white anatase pigment were to remove iron, a major element in the ilmenite starting material, and to prevent the formation of rutile during the final calcination step; the early experimental pigments typically were not bright white as they contained impurities such as residual iron as well as some rutile. For at least a decade from about 1908 onward, laboratory research into possible purification and production methods was being conducted in Europe and the United States. Although the first commercial product was a less than pure pigment (the Prima X line, 83% TiO2) produced in Norway (Titan Company A/S) in 1918 to 1919, this was almost immediately replaced by a composite pigment containing calcium phosphate and barium sulfate in 1919; the early composites were described as the color of “old India ivory.” In the United States (Titanium Pigment Company), pure pigment was only produced in small experimental batches until 1926 (Titanox A, 98% TiO2), and the pigments which were commercially available from 1916 until 1925 were composites with barium sulphate. The Americans eventually adopted the Norwegian technology and the two companies amalgamated in 1920. In France, | + | Anatase was produced synthetically in the early 20th century for use as a white paint pigment with remarkable hiding power. The most successful processes were based on extraction from crushed and roasted ilmenite (iron titanate) using sulfuric acid (sulfate process). The major problems in producing a white anatase pigment were to remove iron, a major element in the ilmenite starting material, and to prevent the formation of rutile during the final calcination step; the early experimental pigments typically were not bright white as they contained impurities such as residual iron as well as some rutile. For at least a decade from about 1908 onward, laboratory research into possible purification and production methods was being conducted in Europe and the United States. Although the first commercial pure anatase product was a less than pure pigment (the Kronos Prima X line, 83% TiO2) produced in Norway (Titan Company A/S) in 1918 to 1919, this was almost immediately replaced by a composite pigment containing calcium phosphate and barium sulfate in 1919 (Kronos Extra X with 69% titanium dioxide); the early composites were described as the color of “old India ivory.” In the United States (Titanium Pigment Company), pure pigment was only produced in small experimental batches until 1926 (Titanox A, 98% TiO2), and the pigments which were commercially available from 1916 until 1925 were composites with barium sulphate (including Titanox BX, 16% titanium dioxide, which was soon discontinued in favor of Titanox BXX, 25% titanium dioxide). The Americans eventually adopted the Norwegian technology and the two companies amalgamated in 1920. In France, the Blumenfeld process was discovered in 1920 to allow production of pure anatase titanium dioxide pigment (Societe de Produits Chimiques des Terres Rares), but only in 1923 did production of 96-99% titanium dioxide pigment begin (Blanc de Thann Or EB and Or P); the pure anatase had significantly greater hiding power than the composites. Pigment purity continued to be a problem, however, and even by 1927 the pure anatase produced at Thann in France was described as slightly yellow. Because rutile had advantageous weathering properties (less chalking) and higher hiding power (up to 25% improvement over pure anatase), research to improve experimental rutile-based pigments that were patented in 1931 culminated in commercial production in Europe and in the United States in 1937. Although rutile products now dominate the market, anatase-based pigments continue to be produced. |

The possibility has been raised that at least one artist (unnamed), who was a friend of Rossi (one of the early researchers in the United States), was given some early experimental pigment (date and composition unknown) to try in an artistic application. Until the commercial production of composites in 1916, these pigments comprised small batches of a few pounds only, and although it is possible that this limited distribution could have been occurring as early as about 1912, it is extremely unlikely that more than a few artists (and perhaps just the one) were involved, and they would have been connected with the researchers in some way. | The possibility has been raised that at least one artist (unnamed), who was a friend of Rossi (one of the early researchers in the United States), was given some early experimental pigment (date and composition unknown) to try in an artistic application. Until the commercial production of composites in 1916, these pigments comprised small batches of a few pounds only, and although it is possible that this limited distribution could have been occurring as early as about 1912, it is extremely unlikely that more than a few artists (and perhaps just the one) were involved, and they would have been connected with the researchers in some way. | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

octahedrite; titanium dioxide; anatase (Eng., Fr., Port., Nor.); anastase (sp); Anatas (Deut.); anatasio (It.); anatasa (Esp.); anataas (Ned.) | octahedrite; titanium dioxide; anatase (Eng., Fr., Port., Nor.); anastase (sp); Anatas (Deut.); anatasio (It.); anatasa (Esp.); anataas (Ned.) | ||

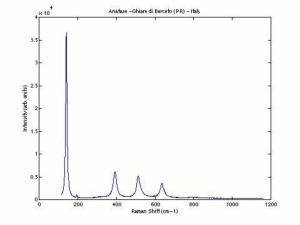

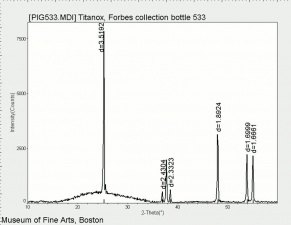

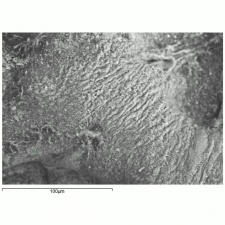

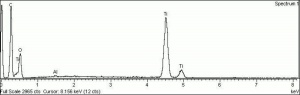

| − | [[[SliderGallery rightalign|Anataseitaly1.jpg~Raman | + | [[[SliderGallery rightalign|Anataseitaly1.jpg~Raman|PIG533.jpg~XRD|f533sem.jpg~SEM|f533edsbw.jpg~EDS]]] |

| + | == Risks == | ||

| − | == | + | Nontoxic. No significant hazards. |

| + | == Physical and Chemical Properties == | ||

Tetragonal crystal system. | Tetragonal crystal system. | ||

| − | Optic sign uniaxial, negative. | + | Optic sign uniaxial, negative. |

| − | Particle size of modern pigment 0.2 - 0.5 micrometers. | + | Particle size of modern pigment 0.2 - 0.5 micrometers; composites up to 0.8 micrometers. |

High birefringence under crossed polars. | High birefringence under crossed polars. | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

At high temperatures (400-1200C) anatase will convert to rutile. | At high temperatures (400-1200C) anatase will convert to rutile. | ||

| + | Chemically inert, insoluble in water, organic solvents, aqueous alkalis; can be dissolved in sulfuric or hydrofluoric acid; slow to dry in oil without additives or surface treatment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Absorbs strongly in the UV, is photochemically active and can cause deterioration of admixed media if exposed to ultraviolet light; early anatase pigments showed considerable tendency to chalk on exposure and could discolor. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 35: | Line 40: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Mohs Hardness | ! scope="row"| Mohs Hardness | ||

| − | | 5. | + | | 5.5 - 6.0 |

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Melting Point | ! scope="row"| Melting Point | ||

| − | | transforms to rutile | + | | n/a (transforms to rutile) |

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Density | ! scope="row"| Density | ||

| − | | 3. | + | | mineral 3.97; coated pigment 3.7 |

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Refractive Index | ! scope="row"| Refractive Index | ||

| − | | 2.54 - 2. | + | | mineral 2.54-2.56; pure pigment (e.g., Titanox A) 2.3-2.65; composite (e.g., Titanox B/C) 1.87-2.3 |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Comparisons == | == Comparisons == | ||

| Line 65: | Line 56: | ||

[[media:download_file_507.pdf|Characteristics of Common White Pigments]] | [[media:download_file_507.pdf|Characteristics of Common White Pigments]] | ||

| + | ==Resources and Citations== | ||

| + | * M.Laver, "Titanium Dioxide Whites", ''Artists Pigments'', Volume 3, E. West FitzHugh (ed.), Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1997. | ||

| − | + | * Walter C. McCrone, "Polarized Light Microscopy in Conservation: A Personal Perspective" ''JAIC'' 33(2):101-14, 1994. (contains a table of dates on the history of titanium white as a pigment) | |

| − | |||

* Nicholas Eastaugh, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, Ruth Siddall, ''Pigment Compendium'', Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2004 | * Nicholas Eastaugh, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, Ruth Siddall, ''Pigment Compendium'', Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2004 | ||

| Line 73: | Line 65: | ||

* G.S.Brady, ''Materials Handbook'', McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1971 Comment: p. 815 | * G.S.Brady, ''Materials Handbook'', McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1971 Comment: p. 815 | ||

| − | * ''Encyclopedia Britannica'', http://www.britannica.com Comment: "anatase" | + | * ''Encyclopedia Britannica'', http://www.britannica.com Comment: "anatase" [Accessed January 22, 2002].; |

* R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, ''Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia'', Dover Publications, New York, 1966 Comment: Ref. Index = 2.5; density = 3.9 | * R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, ''Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia'', Dover Publications, New York, 1966 Comment: Ref. Index = 2.5; density = 3.9 | ||

| Line 83: | Line 75: | ||

* ''Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics'', Elisabeth West FitzHugh, Oxford University Press, Oxford, Vol. 3, 1997 Comment: M.Laver, "Titanium Dioxide Whites" | * ''Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics'', Elisabeth West FitzHugh, Oxford University Press, Oxford, Vol. 3, 1997 Comment: M.Laver, "Titanium Dioxide Whites" | ||

| − | * Wikipedia | + | * Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatase |

* Richard S. Lewis, ''Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary'', Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 10th ed., 1993 | * Richard S. Lewis, ''Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary'', Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 10th ed., 1993 | ||

| − | * | + | *Pigments Through the Ages at http://webexhibits.org/pigments : Refractive index: anatase: 2.3 - 2.65 |

* Buzgar et al., "The Raman Study of the White Pigment used in Cucuteni Pottery," Analele Stiintifice ale Universitatii “Al. I. Cuza” din Iasi Seria Geologie 59(2) 2013) 41–50; also http://geology.uaic.ro/auig/articole/2013%20no2/1_L03-Buzgar.pdf | * Buzgar et al., "The Raman Study of the White Pigment used in Cucuteni Pottery," Analele Stiintifice ale Universitatii “Al. I. Cuza” din Iasi Seria Geologie 59(2) 2013) 41–50; also http://geology.uaic.ro/auig/articole/2013%20no2/1_L03-Buzgar.pdf | ||

Latest revision as of 09:25, 29 August 2020

Description

Anatase, Rutile and Brookite are three naturally occurring isomorphic forms of Titanium dioxide. Anatase forms translucent or transparent crystals (octahedrite) varying in color from black to reddish brown, yellowish brown, dark blue or gray. Deposits have been found in the Alps, Brazil, and the Ural Mountains; it is also formed by the weathering of titanite (sphene) and ilmenite. Mineral anatase is not a major component of artists' materials; however, it has been reported as a minor constituent (<2%) in white paints on ancient artifacts from diverse sites, as a mineral impurity in white clay-based pigments.

Anatase was produced synthetically in the early 20th century for use as a white paint pigment with remarkable hiding power. The most successful processes were based on extraction from crushed and roasted ilmenite (iron titanate) using sulfuric acid (sulfate process). The major problems in producing a white anatase pigment were to remove iron, a major element in the ilmenite starting material, and to prevent the formation of rutile during the final calcination step; the early experimental pigments typically were not bright white as they contained impurities such as residual iron as well as some rutile. For at least a decade from about 1908 onward, laboratory research into possible purification and production methods was being conducted in Europe and the United States. Although the first commercial pure anatase product was a less than pure pigment (the Kronos Prima X line, 83% TiO2) produced in Norway (Titan Company A/S) in 1918 to 1919, this was almost immediately replaced by a composite pigment containing calcium phosphate and barium sulfate in 1919 (Kronos Extra X with 69% titanium dioxide); the early composites were described as the color of “old India ivory.” In the United States (Titanium Pigment Company), pure pigment was only produced in small experimental batches until 1926 (Titanox A, 98% TiO2), and the pigments which were commercially available from 1916 until 1925 were composites with barium sulphate (including Titanox BX, 16% titanium dioxide, which was soon discontinued in favor of Titanox BXX, 25% titanium dioxide). The Americans eventually adopted the Norwegian technology and the two companies amalgamated in 1920. In France, the Blumenfeld process was discovered in 1920 to allow production of pure anatase titanium dioxide pigment (Societe de Produits Chimiques des Terres Rares), but only in 1923 did production of 96-99% titanium dioxide pigment begin (Blanc de Thann Or EB and Or P); the pure anatase had significantly greater hiding power than the composites. Pigment purity continued to be a problem, however, and even by 1927 the pure anatase produced at Thann in France was described as slightly yellow. Because rutile had advantageous weathering properties (less chalking) and higher hiding power (up to 25% improvement over pure anatase), research to improve experimental rutile-based pigments that were patented in 1931 culminated in commercial production in Europe and in the United States in 1937. Although rutile products now dominate the market, anatase-based pigments continue to be produced.

The possibility has been raised that at least one artist (unnamed), who was a friend of Rossi (one of the early researchers in the United States), was given some early experimental pigment (date and composition unknown) to try in an artistic application. Until the commercial production of composites in 1916, these pigments comprised small batches of a few pounds only, and although it is possible that this limited distribution could have been occurring as early as about 1912, it is extremely unlikely that more than a few artists (and perhaps just the one) were involved, and they would have been connected with the researchers in some way.

Synonyms and Related Terms

octahedrite; titanium dioxide; anatase (Eng., Fr., Port., Nor.); anastase (sp); Anatas (Deut.); anatasio (It.); anatasa (Esp.); anataas (Ned.)

Risks

Nontoxic. No significant hazards.

Physical and Chemical Properties

Tetragonal crystal system.

Optic sign uniaxial, negative.

Particle size of modern pigment 0.2 - 0.5 micrometers; composites up to 0.8 micrometers.

High birefringence under crossed polars.

Non-fluorescent to weak white fluorescence (pigment).

At high temperatures (400-1200C) anatase will convert to rutile.

Chemically inert, insoluble in water, organic solvents, aqueous alkalis; can be dissolved in sulfuric or hydrofluoric acid; slow to dry in oil without additives or surface treatment.

Absorbs strongly in the UV, is photochemically active and can cause deterioration of admixed media if exposed to ultraviolet light; early anatase pigments showed considerable tendency to chalk on exposure and could discolor.

| Composition | TiO2 |

|---|---|

| Mohs Hardness | 5.5 - 6.0 |

| Melting Point | n/a (transforms to rutile) |

| Density | mineral 3.97; coated pigment 3.7 |

| Refractive Index | mineral 2.54-2.56; pure pigment (e.g., Titanox A) 2.3-2.65; composite (e.g., Titanox B/C) 1.87-2.3 |

Comparisons

Characteristics of Common White Pigments

Resources and Citations

- M.Laver, "Titanium Dioxide Whites", Artists Pigments, Volume 3, E. West FitzHugh (ed.), Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1997.

- Walter C. McCrone, "Polarized Light Microscopy in Conservation: A Personal Perspective" JAIC 33(2):101-14, 1994. (contains a table of dates on the history of titanium white as a pigment)

- Nicholas Eastaugh, Valentine Walsh, Tracey Chaplin, Ruth Siddall, Pigment Compendium, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2004

- G.S.Brady, Materials Handbook, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1971 Comment: p. 815

- Encyclopedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com Comment: "anatase" [Accessed January 22, 2002].;

- R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia, Dover Publications, New York, 1966 Comment: Ref. Index = 2.5; density = 3.9

- Dictionary of Building Preservation, Ward Bucher, ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York City, 1996

- Thomas B. Brill, Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities, Plenum Press, New York City, 1980 Comment: Ref. index = 2.56, 2.49

- Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, Elisabeth West FitzHugh, Oxford University Press, Oxford, Vol. 3, 1997 Comment: M.Laver, "Titanium Dioxide Whites"

- Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatase

- Richard S. Lewis, Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 10th ed., 1993

- Pigments Through the Ages at http://webexhibits.org/pigments : Refractive index: anatase: 2.3 - 2.65

- Buzgar et al., "The Raman Study of the White Pigment used in Cucuteni Pottery," Analele Stiintifice ale Universitatii “Al. I. Cuza” din Iasi Seria Geologie 59(2) 2013) 41–50; also http://geology.uaic.ro/auig/articole/2013%20no2/1_L03-Buzgar.pdf