Difference between revisions of "Diamond"

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

[[File:Diamond.ring.jpg|thumb|Diamond ring]] | [[File:Diamond.ring.jpg|thumb|Diamond ring]] | ||

| + | [[File:diamondswkp.jpg|thumb|Diamonds]] | ||

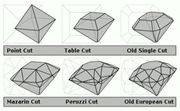

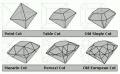

| + | [[File:DiamondcutWK.jpg|thumb|Diamond cuts]] | ||

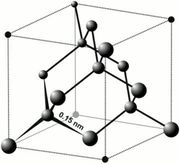

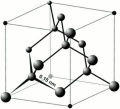

| + | [[File:diamondunitcellWK.jpg|thumb|Diamond unit cell]] | ||

A stable, extremely hard, crystalline form of [[carbon]] that occurs naturally. Diamonds were known to man prior to 800 BCE from alluvial deposits found in India, Sumatra, and Borneo. They were discovered in Brazil in 1725, in South Africa in 1867, and in Arkansas in 1906. The finest grade diamonds are transparent, brilliant stones that are used as gems; these are primarily mined from the kimberlite pipes in South Africa, and glacial tills of Zaire and Brazil. The largest diamond in the world, the Cullinan diamond, was found in 1905 in South Africa. Named for Sir Thomas Cullinan, it has since been cut into 9 large stones, the largest of which, Great Star of Africa (530.2 carat), is set in the British royal scepter. Diamonds with some imperfections are classified as industrial grade and are used for cutting tools and delicate instruments. These are primarily mined in Australia, Brazil, and South Africa. Abrasive pastes are made from small, imperfectly crystallized pieces called [[bort]] (rounded with no distinct cleavage), [[ballas]], and [[carbonado]] (black diamond, usually granular with no distinct cleavage). Synthetic diamonds, produced using high heat and pressure, are also used as abrasives. Imitation diamonds have been made from lead glass ([[paste diamond]]), quartz rock crystal ([[rhinestone]]), cubic [[Zirconium oxide |zirconia]], synthetic [[rutile]], and synthetic [[spinel]]. | A stable, extremely hard, crystalline form of [[carbon]] that occurs naturally. Diamonds were known to man prior to 800 BCE from alluvial deposits found in India, Sumatra, and Borneo. They were discovered in Brazil in 1725, in South Africa in 1867, and in Arkansas in 1906. The finest grade diamonds are transparent, brilliant stones that are used as gems; these are primarily mined from the kimberlite pipes in South Africa, and glacial tills of Zaire and Brazil. The largest diamond in the world, the Cullinan diamond, was found in 1905 in South Africa. Named for Sir Thomas Cullinan, it has since been cut into 9 large stones, the largest of which, Great Star of Africa (530.2 carat), is set in the British royal scepter. Diamonds with some imperfections are classified as industrial grade and are used for cutting tools and delicate instruments. These are primarily mined in Australia, Brazil, and South Africa. Abrasive pastes are made from small, imperfectly crystallized pieces called [[bort]] (rounded with no distinct cleavage), [[ballas]], and [[carbonado]] (black diamond, usually granular with no distinct cleavage). Synthetic diamonds, produced using high heat and pressure, are also used as abrasives. Imitation diamonds have been made from lead glass ([[paste diamond]]), quartz rock crystal ([[rhinestone]]), cubic [[Zirconium oxide |zirconia]], synthetic [[rutile]], and synthetic [[spinel]]. | ||

Revision as of 12:46, 13 October 2024

Description

A stable, extremely hard, crystalline form of Carbon that occurs naturally. Diamonds were known to man prior to 800 BCE from alluvial deposits found in India, Sumatra, and Borneo. They were discovered in Brazil in 1725, in South Africa in 1867, and in Arkansas in 1906. The finest grade diamonds are transparent, brilliant stones that are used as gems; these are primarily mined from the kimberlite pipes in South Africa, and glacial tills of Zaire and Brazil. The largest diamond in the world, the Cullinan diamond, was found in 1905 in South Africa. Named for Sir Thomas Cullinan, it has since been cut into 9 large stones, the largest of which, Great Star of Africa (530.2 carat), is set in the British royal scepter. Diamonds with some imperfections are classified as industrial grade and are used for cutting tools and delicate instruments. These are primarily mined in Australia, Brazil, and South Africa. Abrasive pastes are made from small, imperfectly crystallized pieces called Bort (rounded with no distinct cleavage), Ballas, and Carbonado (black diamond, usually granular with no distinct cleavage). Synthetic diamonds, produced using high heat and pressure, are also used as abrasives. Imitation diamonds have been made from lead glass (Paste diamond), quartz rock crystal (Rhinestone), cubic zirconia, synthetic Rutile, and synthetic Spinel.

Properties of Natural and Simulated Diamonds

| Gem | Source | Composition | Common dates of use | Mohs' hardness | Refractive index | Specific gravity | Dispersion | Crystal indices | Fluorescence | Optical | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corundum | natural or synthetic | Al2O3 | 1900- 1947 |

9 | epsilon = 1.757-1.768; omega = 1.765-1.776 |

3.96- 4.05 |

0.018 | hexagonal crystal system with tabular, prismatic or pyramidal crystals; fracture = conchoidal |

orange to red; heat treated stones may fluoresce green | marked dichroism | natural inclusions minerals and fluid are common; synthetic may have gas bubbles and curved striae; low thermal conductivity |

| Cubic zirconia | synthetic | ZrSiO4 | 1976 - present |

8.5 | 2.15-2.18 | 5.6-6.0 | 0.06 | fracture = conchoidal | yellow fluorescence in shortwave UV | usually no inclusions; low thermal conductivity | |

| Diamond | natural | C | 1476 - present |

10 | 2.4175 | 3.51- 3.53 |

0.044 | cubic crystal system; perfect cleavage in four directions. | may fluoresce pale colors in longwave UV; may phosphoresce | Numerous inclusions; trigonal on surface; very high thermal conductivity | |

| Garnet | synthetic | YAG/GGG | 1970- 1976 |

8.25/7.0 | 1.87/1.97 | 4.6/7.0 | 0.028/ 0.045 |

cubic crystal system | isotropic | turns brown in UV light; low thermal conductivity | |

| Moissanite | synthetic | silicon carbide | 1998 - present |

8.5-8.25 | 2.65-2.69 | 3.22 | 0.104 | may have pale fluorescence | strongly birefringent; anisotropic | may have brown tint; resistant to heat; inclusions occur as fine white tubes; high thermal conductivity | |

| Paste diamond | synthetic | high lead glass | 1700 - present |

5.0-6.0 | 1.67 | 2.4-4.2 | >0.02 | highly refractive | low thermal conductivity; used since 1700 | ||

| Quartz | natural | SiO2 | 7 | epsilon = 1.553; omega = 1.544 |

2.65- 2.66 |

trigonal crystal system; low birefringence; fracture = conchoidal |

low birefringence | heat treatments may bleach stones; low thermal conductivity; low thermal expansion; | |||

| Rutile | synthetic | TiO2 | 1947- 1955 |

6 | 2.6-2.9 | 4.25 | 0.33 | doubly refractive | may have yellow tint; low thermal conductivity | ||

| Spinel | natural or synthetic | MgAl2O4 | 1920- 1947 |

8 | 1.715-1.725 | 3.5-4.1 | 0.02 | isometric crystal system; fracture = conchoidal | natural fluoresces red in longwave; synthetic may fluoresce in shortwave |

anisotropic | Natural stone has octahedral inclusions; may have fingerprint patterns; low thermal conductivity |

| Strontium titantate | synthetic | SrTiO3 | 1955- 1970 |

5.5 | 2.41 | 5.13 | 0.19 | low thermal conductivity | |||

| Tourmaline | natural | aluminum borosilicate | 7-7.5 | epsilon = 1.610-1.650; omega = 1.635-1.675 |

2.9-3.2 | hexagonal, prismatic crystals; fracture = conchoidal | little fluorescence | pleochroic; high birefringence | inclusions include gas or liquid pockets and color zoning; develops electrical charge when heated | ||

| Zircon | natural | ZrSiO4 | 6.0 - 7.5 | epsilon = 1.968-2.015; omega = 1.923-1.960 |

4.6-4.7 | 0.039 | tetragonal system with square prismatic crystals; brittle; fracture = uneven | some show dull yellow color; some may phosphoresce | pleochroic; high birefringence | heating brown zircon crystals produces strong colors (blue, green, red, etc.) that fade slowly with time or with UV exposure; low thermal conductivity |

Synonyms and Related Terms

bort; carbonado; ballas; Cullinan diamond; Great Star of Africa; adamas (ancient Greek); diamant (Ces., Dan., Fr., Ned., Sven.); Diamant (Deut.); diamante (Esp., It., Port.); diament (Pol.)

Risks

- No significant hazards.

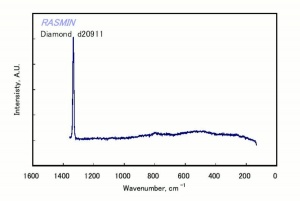

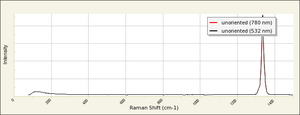

Physical and Chemical Properties

- Hardest natural material.

- Cubic crystal system.

- Perfect cleavage in four directions.

- Luster = greasy to adamantine.

- Streak = colorless.

- Fluorescence: natural diamonds may fluoresce blue (type I) or orange (type II). Irradiated diamonds have a strong orange fluorescence in both LW and SW, Synthetic diamonds range from inert to strong orange fluorescence; some may phosphoresce.

- Birefringence = none

| Mohs Hardness | 10 |

|---|---|

| Melting Point | 3700 C |

| Boiling Point | 4200 C |

| Density | 3.51-3.53 g/ml |

| Refractive Index | 2.417-2.4195 |

| Dispersion | 0.044 (moderate fire) |

For easy print and to download

Properties of Common Abrasives

Properties of Common Gemstones

Natural and Simulated Diamonds

Additional Images

Resources and Citations

- Gem Identification Lab Manual, Gemological Institute of America, 2016. (fluorescence information)

- Mineralogy Database: Diamond

- Jack Odgen, Jewellery of the Ancient World, Rizzoli International Publications Inc., New York City, 1982

- R.F.Symmes, T.T.Harding, Paul Taylor, Rocks, Fossils and Gems, DK Publishing, Inc., New York City, 1997

- Encyclopedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com Comment: "diamond" [Accessed March 4, 2002].

- Website: http://www.geo.utexas.edu/courses/347k/redesign/gem_notes/Diamond/diamond_triple_frame.htm (fluorescence information)

- Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diamond (Accessed Mar. 1, 2006) (synonyms)

- Yasukazu Suwa, Gemstones: Quality and Value, Volume 1, Sekai Bunka Publishing Inc., Tokyo, 1999 Comment: RI=2.417; Specific gravity=3.52;

- Michael O'Donoghue and Louise Joyner, Identification of Gemstones, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2003 Comment: RI=2.417; Specific gravity=3.52; dispersion=0.44

- Van Nostrand's Scientific Encyclopedia, Douglas M. Considine (ed.), Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 1976

- The American Heritage Dictionary or Encarta, via Microsoft Bookshelf 98, Microsoft Corp., 1998

- G.S.Brady, Materials Handbook, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1971

- Michael McCann, Artist Beware, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York City, 1979

- R.M.Organ, Design for Scientific Conservation of Antiquities, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, 1968

- Thomas B. Brill, Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities, Plenum Press, New York City, 1980

- CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, Robert Weast (ed.), CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida, v. 61, 1980 Comment: density=3.01-3.52