Difference between revisions of "Naples yellow"

| (3 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

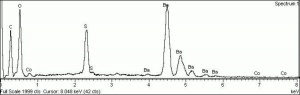

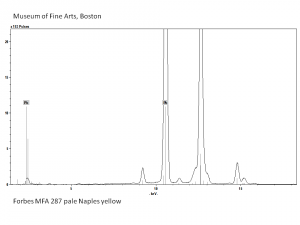

[[File:287 pale naples yellow.jpg|thumb|Naples yellow]] | [[File:287 pale naples yellow.jpg|thumb|Naples yellow]] | ||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

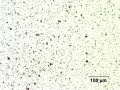

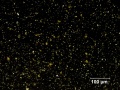

| − | + | [[File:Jauneantim C100x.jpg|thumb|Jaune antimoine (Forbes 294) at 100x (visible light left; UV light right)]] | |

A synthetic pigment composed of [[lead antimonate yellow]], which is produced in colors ranging from lemon yellow for the very pure pigment to darker shades. Naples yellow pigments with a greenish, pinkish orange, or reddish tinge have been produced; the color depends on the method and temperature of manufacture. It has been used as a colorant for glass, ceramic tiles, and paint for at least 3500 years. Lead antimonate yellow has been identified in objects from Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Babylonian, Greek, Roman, and Celtic cultures. In Western European art, Naples yellow has been used in [[majolica]] pottery glazes since about 1500 and in paintings dating from about 1600. It was most frequently used during the period 1750-1850 after which it was gradually replaced by other yellow pigments. Naples yellow is a synthetic pigment with the chemical formula, Pb2Sb2O7. It has a crystal structure similar to the mineral bindheimite; the naturally occurring mineral is not used as a pigment however. Since other yellowish minerals occur on Mount Vesuvius near Naples it seems plausible that this association might explain the name "Naples Yellow." There is yet no documentary or analytical evidence to support this hypothesis. The raw materials and manufacturing processes for making zalulino (another name for lead antimonate yellow) were first published in 1556 by Cipriano Piccolpasso of Castel Durante, Italy, in his treatise ''Le Tre Libri dell'Arte del Vasaio'' (The Three Books of the Potter's Art). In 1758, Giambattista Passeri published very similar recipes for the pigment giallolino. Piccolpasso's recipes call for heating a mixture of [[lead]], [[antimony]], [[lees]], and [[salt]]. Scientific studies of Naples yellow include those published in France by Auguste-Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy (1766) and Léonor Mérimée (1839) and in Switzerland by Karl Brunner (1837). Before Naples yellow came into widespread use in the 18th century, [[lead-tin yellow]] was the pigment most used by artists in Europe starting in about 1300. Lead-tin yellow was rediscovered in 1941 by Richard Jacobi of the Doerner Institut, Munich using x-ray diffraction analysis. Until then, it was not generally understood that there were at lease three distinct yellow pigments composed of lead compounds: lead antimonate yellow, lead-tin yellow type I and lead-tin yellow type II. More recently, scientists have found pigments which made of lead-antimony-tin oxide compounds. Genuine Naples yellow continued to be sold during the 20th century but the name "Naples Yellow" came to indicate a color shade that is commercially produced by mixing together other pigments, such as [[cadmium yellow]], [[zinc white]], and [[Venetian red]]. Naples yellow is lightfast and chemically stable, but may darken with high temperatures, or exposure to [[iron]] compounds or [[sulfur]] fumes. | A synthetic pigment composed of [[lead antimonate yellow]], which is produced in colors ranging from lemon yellow for the very pure pigment to darker shades. Naples yellow pigments with a greenish, pinkish orange, or reddish tinge have been produced; the color depends on the method and temperature of manufacture. It has been used as a colorant for glass, ceramic tiles, and paint for at least 3500 years. Lead antimonate yellow has been identified in objects from Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Babylonian, Greek, Roman, and Celtic cultures. In Western European art, Naples yellow has been used in [[majolica]] pottery glazes since about 1500 and in paintings dating from about 1600. It was most frequently used during the period 1750-1850 after which it was gradually replaced by other yellow pigments. Naples yellow is a synthetic pigment with the chemical formula, Pb2Sb2O7. It has a crystal structure similar to the mineral bindheimite; the naturally occurring mineral is not used as a pigment however. Since other yellowish minerals occur on Mount Vesuvius near Naples it seems plausible that this association might explain the name "Naples Yellow." There is yet no documentary or analytical evidence to support this hypothesis. The raw materials and manufacturing processes for making zalulino (another name for lead antimonate yellow) were first published in 1556 by Cipriano Piccolpasso of Castel Durante, Italy, in his treatise ''Le Tre Libri dell'Arte del Vasaio'' (The Three Books of the Potter's Art). In 1758, Giambattista Passeri published very similar recipes for the pigment giallolino. Piccolpasso's recipes call for heating a mixture of [[lead]], [[antimony]], [[lees]], and [[salt]]. Scientific studies of Naples yellow include those published in France by Auguste-Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy (1766) and Léonor Mérimée (1839) and in Switzerland by Karl Brunner (1837). Before Naples yellow came into widespread use in the 18th century, [[lead-tin yellow]] was the pigment most used by artists in Europe starting in about 1300. Lead-tin yellow was rediscovered in 1941 by Richard Jacobi of the Doerner Institut, Munich using x-ray diffraction analysis. Until then, it was not generally understood that there were at lease three distinct yellow pigments composed of lead compounds: lead antimonate yellow, lead-tin yellow type I and lead-tin yellow type II. More recently, scientists have found pigments which made of lead-antimony-tin oxide compounds. Genuine Naples yellow continued to be sold during the 20th century but the name "Naples Yellow" came to indicate a color shade that is commercially produced by mixing together other pigments, such as [[cadmium yellow]], [[zinc white]], and [[Venetian red]]. Naples yellow is lightfast and chemically stable, but may darken with high temperatures, or exposure to [[iron]] compounds or [[sulfur]] fumes. | ||

| − | |||

== Synonyms and Related Terms == | == Synonyms and Related Terms == | ||

lead antimonate yellow; Pigment Yellow 41; CI 77588; lead antimony oxide; antimony yellow; zalulino; amarillo de Nápoles (Esp.); jaune d'antimoine (Fr.); jaune de Naples (Fr.); Antimongelb (Deut.); Bleintimoniat (Deut.); Neapelgelb (Deut.); kitrino ths Napolis (Gr.); giallo di Napoli (giallorino) (It.); napelsgeel (Ned.); amarelo de Nápoles (Port.); brilliant yellow; jaune brilliant; giallolino (also applied to lead-tin yellow); giallorino (also applied to lead-tin yellow); | lead antimonate yellow; Pigment Yellow 41; CI 77588; lead antimony oxide; antimony yellow; zalulino; amarillo de Nápoles (Esp.); jaune d'antimoine (Fr.); jaune de Naples (Fr.); Antimongelb (Deut.); Bleintimoniat (Deut.); Neapelgelb (Deut.); kitrino ths Napolis (Gr.); giallo di Napoli (giallorino) (It.); napelsgeel (Ned.); amarelo de Nápoles (Port.); brilliant yellow; jaune brilliant; giallolino (also applied to lead-tin yellow); giallorino (also applied to lead-tin yellow); | ||

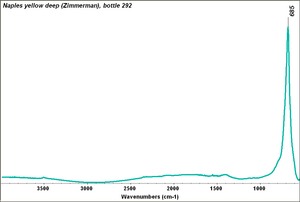

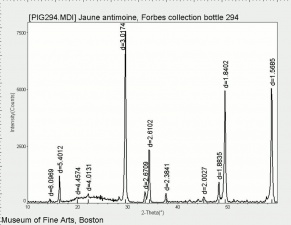

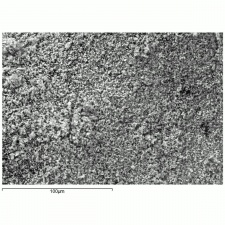

| − | [[[SliderGallery rightalign| | + | [[[SliderGallery rightalign|Naples yellow 292.TIF~FTIR (MFA)|Naples yellow (Forbes MFA 293) 50X, 532 nm resize.tif~Raman (MFA)|NMFA- Naples yellow deep.jpg~FTIR|PIG294.jpg~XRD|f289sem.jpg~SEM|f289edsbw.jpg~EDS|Slide1 FC287.PNG~XRF]]] |

| − | == | + | == Risks == |

| − | + | * Toxic by ingestion and inhalation. | |

| + | * Carcinogen, teratogen, suspected mutagen. | ||

| − | Can turn black in the presence of sulfur or iron. | + | ==Physical and Chemical Properties== |

| + | |||

| + | * Insoluble in water and dilute acids. | ||

| + | * Can turn black in the presence of sulfur or iron. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 26: | Line 29: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Density | ! scope="row"| Density | ||

| − | | 6.58 | + | | 6.58 g/ml |

|- | |- | ||

! scope="row"| Refractive Index | ! scope="row"| Refractive Index | ||

| 2.01 - 2.88 | | 2.01 - 2.88 | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Additional Images == | == Additional Images == | ||

| Line 52: | Line 45: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Resources and Citations== |

| − | * | + | * I.N.M.Wainwright, J.M.Taylor, R.D.Harley, "Lead Antimonate Yellow", ''Artists Pigments'', Volume 1, R. Feller (ed.), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1986. "..highest popularity in European art between approx. 1750-1850.." |

| − | * | + | * J. Dik, E. Hermens, R. Peschar, and H. Schenk, 'Early production recipes for lead antimonate yellow in Italian art', ''Archaeometry'', 47, 2005, 593-607. |

| + | |||

| + | * Ian Wainwright, Contributed information , December 2007 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Ashok Roy, Contributed information, November 2007 | ||

* R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, ''Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia'', Dover Publications, New York, 1966 | * R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, ''Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia'', Dover Publications, New York, 1966 | ||

| − | * '' | + | * Thomas B. Brill, ''Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities'', P |

* M. Doerner, ''The Materials of the Artist'', Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1934 | * M. Doerner, ''The Materials of the Artist'', Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1934 | ||

| Line 80: | Line 77: | ||

* ''The Merck Index'', Martha Windholz (ed.), Merck Research Labs, Rahway NJ, 10th edition, 1983 Comment: entry 5412 | * ''The Merck Index'', Martha Windholz (ed.), Merck Research Labs, Rahway NJ, 10th edition, 1983 Comment: entry 5412 | ||

| − | * Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, | + | * Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabulary/aat/, J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles, 2000 |

| − | * | + | * Pigments Through the Ages - http://webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/naplesyellow.html Refractive index: 2.01 - 2.28 |

| − | * R. Newman, E. Farrell, 'House Paint Pigments', ''Paint in America '', R. | + | * R. Newman, E. Farrell, 'House Paint Pigments', ''Paint in America '', R. lenum Press, New York City, 1980 Comment: synthetically produced in 1758 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

* ''The Dictionary of Art'', Grove's Dictionaries Inc., New York, 1996 Comment: "Pigments" | * ''The Dictionary of Art'', Grove's Dictionaries Inc., New York, 1996 Comment: "Pigments" | ||

| − | + | Record content reviewed by EU-Artech, January 2008. | |

[[Category:Materials database]] | [[Category:Materials database]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:04, 19 October 2022

Description

A synthetic pigment composed of Lead antimonate yellow, which is produced in colors ranging from lemon yellow for the very pure pigment to darker shades. Naples yellow pigments with a greenish, pinkish orange, or reddish tinge have been produced; the color depends on the method and temperature of manufacture. It has been used as a colorant for glass, ceramic tiles, and paint for at least 3500 years. Lead antimonate yellow has been identified in objects from Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Babylonian, Greek, Roman, and Celtic cultures. In Western European art, Naples yellow has been used in Majolica pottery glazes since about 1500 and in paintings dating from about 1600. It was most frequently used during the period 1750-1850 after which it was gradually replaced by other yellow pigments. Naples yellow is a synthetic pigment with the chemical formula, Pb2Sb2O7. It has a crystal structure similar to the mineral bindheimite; the naturally occurring mineral is not used as a pigment however. Since other yellowish minerals occur on Mount Vesuvius near Naples it seems plausible that this association might explain the name "Naples Yellow." There is yet no documentary or analytical evidence to support this hypothesis. The raw materials and manufacturing processes for making zalulino (another name for lead antimonate yellow) were first published in 1556 by Cipriano Piccolpasso of Castel Durante, Italy, in his treatise Le Tre Libri dell'Arte del Vasaio (The Three Books of the Potter's Art). In 1758, Giambattista Passeri published very similar recipes for the pigment giallolino. Piccolpasso's recipes call for heating a mixture of Lead, Antimony, Lees, and Salt. Scientific studies of Naples yellow include those published in France by Auguste-Denis Fougeroux de Bondaroy (1766) and Léonor Mérimée (1839) and in Switzerland by Karl Brunner (1837). Before Naples yellow came into widespread use in the 18th century, Lead-tin yellow was the pigment most used by artists in Europe starting in about 1300. Lead-tin yellow was rediscovered in 1941 by Richard Jacobi of the Doerner Institut, Munich using x-ray diffraction analysis. Until then, it was not generally understood that there were at lease three distinct yellow pigments composed of lead compounds: lead antimonate yellow, lead-tin yellow type I and lead-tin yellow type II. More recently, scientists have found pigments which made of lead-antimony-tin oxide compounds. Genuine Naples yellow continued to be sold during the 20th century but the name "Naples Yellow" came to indicate a color shade that is commercially produced by mixing together other pigments, such as Cadmium yellow, Zinc white, and Venetian red. Naples yellow is lightfast and chemically stable, but may darken with high temperatures, or exposure to Iron compounds or Sulfur fumes.

Synonyms and Related Terms

lead antimonate yellow; Pigment Yellow 41; CI 77588; lead antimony oxide; antimony yellow; zalulino; amarillo de Nápoles (Esp.); jaune d'antimoine (Fr.); jaune de Naples (Fr.); Antimongelb (Deut.); Bleintimoniat (Deut.); Neapelgelb (Deut.); kitrino ths Napolis (Gr.); giallo di Napoli (giallorino) (It.); napelsgeel (Ned.); amarelo de Nápoles (Port.); brilliant yellow; jaune brilliant; giallolino (also applied to lead-tin yellow); giallorino (also applied to lead-tin yellow);

Risks

- Toxic by ingestion and inhalation.

- Carcinogen, teratogen, suspected mutagen.

Physical and Chemical Properties

- Insoluble in water and dilute acids.

- Can turn black in the presence of sulfur or iron.

| Composition | Pb2Sb2O7 |

|---|---|

| CAS | 13510-89-9 |

| Density | 6.58 g/ml |

| Refractive Index | 2.01 - 2.88 |

Additional Images

Resources and Citations

- I.N.M.Wainwright, J.M.Taylor, R.D.Harley, "Lead Antimonate Yellow", Artists Pigments, Volume 1, R. Feller (ed.), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1986. "..highest popularity in European art between approx. 1750-1850.."

- J. Dik, E. Hermens, R. Peschar, and H. Schenk, 'Early production recipes for lead antimonate yellow in Italian art', Archaeometry, 47, 2005, 593-607.

- Ian Wainwright, Contributed information , December 2007

- Ashok Roy, Contributed information, November 2007

- R. J. Gettens, G.L. Stout, Painting Materials, A Short Encyclopaedia, Dover Publications, New York, 1966

- Thomas B. Brill, Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities, P

- M. Doerner, The Materials of the Artist, Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1934

- Reed Kay, The Painter's Guide To Studio Methods and Materials, Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1983

- Ralph Mayer, A Dictionary of Art Terms and Techniques, Harper and Row Publishers, New York, 1969 (also 1945 printing)

- Richard S. Lewis, Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York, 10th ed., 1993

- Michael McCann, Artist Beware, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York City, 1979

- R.D. Harley, Artists' Pigments c. 1600-1835, Butterworth Scientific, London, 1982

- Dictionary of Building Preservation, Ward Bucher, ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York City, 1996

- Robert Fournier, Illustrated Dictionary of Practical Pottery, Chilton Book Company, Radnor, PA, 1992

- The Merck Index, Martha Windholz (ed.), Merck Research Labs, Rahway NJ, 10th edition, 1983 Comment: entry 5412

- Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabulary/aat/, J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles, 2000

- Pigments Through the Ages - http://webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/naplesyellow.html Refractive index: 2.01 - 2.28

- R. Newman, E. Farrell, 'House Paint Pigments', Paint in America , R. lenum Press, New York City, 1980 Comment: synthetically produced in 1758

- The Dictionary of Art, Grove's Dictionaries Inc., New York, 1996 Comment: "Pigments"

Record content reviewed by EU-Artech, January 2008.