Difference between revisions of "Lead-tin yellow"

(username removed) |

|||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

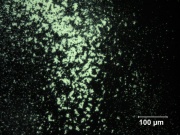

| − | [[File:18_Leadtin_yellow_200X_R.jpg|thumb|Lead-tin yellow]] | + | [[File:18_Leadtin_yellow_200X_R.jpg|thumb|Lead-tin yellow at 200x]] |

== Description == | == Description == | ||

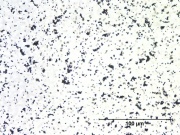

| + | [[File:18_Leadtin_yellow_500X.jpg|thumb|Lead-tin yellow at 500s transmitted light]] | ||

| + | A primrose to canary yellow manufactured pigment composed of lead stannate. Lead-tin yellow was used in European paintings from the beginning of the 14th century until the early years of the 18th century, although it had largely disappeared from painting at the end of the 17th century when it was replaced by [[Naples yellow]] (lead antimonate yellow). Lead-tin yellow was rediscovered and made synthetically in 1941 by Richard Jacobi of the Doerner-Institut in Munich. Two distinct varieties are known, designated ‘type I’ and ‘type II’ in modern terminology. Both types are made by heating together lead and tin oxides in a furnace; for ‘type II’, [[sand]] (silicon dioxide) is included in the starting materials. These yellow pigments are stable and have been used as [[opacifier|opacifiers]] and colorants in [[glass]] and ceramic [[glaze|glazes]]. Lead-tin yellow is made by heating a mixture of [[lead oxide]] with [[stannic oxide|tin dioxide]] to temperatures of 650-800C (type I, tetragonal) or, with silica, to 900-950C (type II, cubic pyrochlore). The two types possess different crystal structures which can be distinguished by [[X-ray diffraction]]. Both types are lightfast and essentially stable in all paint media, although ‘type I’, particularly, has a strong propensity to interact with oil binding media to form colourless ‘inclusions’ now known to be composed of [[lead soap|lead soaps]]. It is an accident of terminology that ‘type II’ has the earlier history enjoying widespread use in the 14th century, then tending to be replaced by ‘type I’ during the second quarter of the 15th century. However both varieties were in use in Venetian painting in the 16th century. Lead-tin yellow was often used in mixtures with other pigments such as [[lead white]], [[vermilion]], [[azurite]], [[verdigris]], and [[indigo]]. | ||

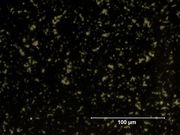

| − | + | [[File:18_Leadtin_yellow_500X_pol.jpg|thumb|Lead-tin yellow at 500x polarized light]] | |

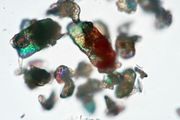

| − | + | [[File:leadtinoxide.jpg|thumb|Lead-tin oxide]] | |

| − | [[File: | ||

== Synonyms and Related Terms == | == Synonyms and Related Terms == | ||

| − | lead stannate; lead tin yellow; jaune de plomb | + | lead stannate; lead tin yellow; jaune de plomb étain (Fr.); Bleinzinngelb (Deut.); amarillo de plomo estano (Esp.); kitrino molybdoy - kassiteroy (Gr.); giallo di piombo e stagno (giallorino) (It.); lood-tingeel (Ned.); amarelo de estanho e chumbo (Port.) |

(It is now generally thought the following historic terms referred to lead-tin yellow: giallolino; giallorino; massicot; masticot) | (It is now generally thought the following historic terms referred to lead-tin yellow: giallolino; giallorino; massicot; masticot) | ||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

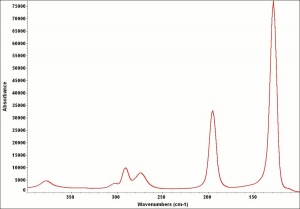

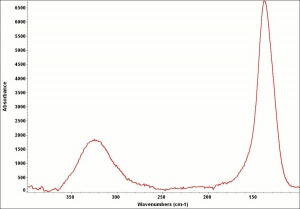

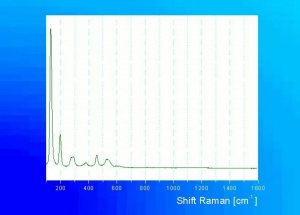

[[[SliderGallery rightalign|Leadtin1UCL.jpg~Raman|Leadtin2UCL.jpg~Raman|leadtinyellow531.jpg~Raman]]] | [[[SliderGallery rightalign|Leadtin1UCL.jpg~Raman|Leadtin2UCL.jpg~Raman|leadtinyellow531.jpg~Raman]]] | ||

| − | == | + | == Risks == |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Toxic by inhalation or ingestion. | |

| + | * Skin contact may cause irritation or ulcers. | ||

| + | * Carcinogen, teratogen, suspected mutagen. | ||

| + | * Darkens when exposed to sulfur fumes. | ||

| − | + | == Physical and Chemical Properties == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | * Unaffected by dilute acids and alkalis. | ||

| + | * Microscopically, lead-tin yellow I has very fine, slightly rounded particles with a high refractive index, while type II usually contains larger, angular particles, sometimes with conchoidal fracture. | ||

| + | * Lead-tin yellow I is birefracting. Lead-tin yellow II is isotropic. | ||

| + | * Composition = Pb2SnO4 (type I); Pb(Sn,Si)O3 (type II) | ||

| + | * Refractive Index = 2.29; 2.31 | ||

| − | == | + | ==Resources and Citations== |

| + | * H. Kuhn, "Lead-Tin Yellow", ''Artists Pigments'', Volume 2, A. Roy (ed.), Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1993. | ||

| − | * '' | + | * E. Martin and A. Duval ‘Les deux variétés de jaune de plomb e d’étain: étude chronologique’, ''Studies in Conservation'', 35, 1990, 117-36. Record content reviewed by EU-Artech, November 2007. |

* ''The Dictionary of Art'', Grove's Dictionaries Inc., New York, 1996 Comment: "Pigments" | * ''The Dictionary of Art'', Grove's Dictionaries Inc., New York, 1996 Comment: "Pigments" | ||

| − | * | + | * Ashok Roy, Contributed information, November 2007 |

| − | * | + | * Michael McCann, ''Artist Beware'', Watson-Guptill Publications, New York City, 1979 |

| − | * | + | * R. Newman, E. Farrell, 'House Paint Pigments', ''Paint in America '', R. Moss ed., Preservation Press, New York City, 1994 |

| − | * | + | * Thomas B. Brill, ''Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities'', Plenum Press, New York City, 1980 |

| − | * | + | * Book and Paper Group, ''Paper Conservation Catalog'', AIC, 1984, 1989 |

| − | * Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, | + | * Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabulary/aat/, J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles, 2000 |

| − | * | + | * Pigments through the Ages http://webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/pbsnyellow.html |

[[Category:Materials database]] | [[Category:Materials database]] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:22, 23 September 2022

Description

A primrose to canary yellow manufactured pigment composed of lead stannate. Lead-tin yellow was used in European paintings from the beginning of the 14th century until the early years of the 18th century, although it had largely disappeared from painting at the end of the 17th century when it was replaced by Naples yellow (lead antimonate yellow). Lead-tin yellow was rediscovered and made synthetically in 1941 by Richard Jacobi of the Doerner-Institut in Munich. Two distinct varieties are known, designated ‘type I’ and ‘type II’ in modern terminology. Both types are made by heating together lead and tin oxides in a furnace; for ‘type II’, Sand (silicon dioxide) is included in the starting materials. These yellow pigments are stable and have been used as opacifiers and colorants in Glass and ceramic glazes. Lead-tin yellow is made by heating a mixture of Lead oxide with tin dioxide to temperatures of 650-800C (type I, tetragonal) or, with silica, to 900-950C (type II, cubic pyrochlore). The two types possess different crystal structures which can be distinguished by X-ray diffraction. Both types are lightfast and essentially stable in all paint media, although ‘type I’, particularly, has a strong propensity to interact with oil binding media to form colourless ‘inclusions’ now known to be composed of lead soaps. It is an accident of terminology that ‘type II’ has the earlier history enjoying widespread use in the 14th century, then tending to be replaced by ‘type I’ during the second quarter of the 15th century. However both varieties were in use in Venetian painting in the 16th century. Lead-tin yellow was often used in mixtures with other pigments such as Lead white, Vermilion, Azurite, Verdigris, and Indigo.

Synonyms and Related Terms

lead stannate; lead tin yellow; jaune de plomb étain (Fr.); Bleinzinngelb (Deut.); amarillo de plomo estano (Esp.); kitrino molybdoy - kassiteroy (Gr.); giallo di piombo e stagno (giallorino) (It.); lood-tingeel (Ned.); amarelo de estanho e chumbo (Port.)

(It is now generally thought the following historic terms referred to lead-tin yellow: giallolino; giallorino; massicot; masticot)

Risks

- Toxic by inhalation or ingestion.

- Skin contact may cause irritation or ulcers.

- Carcinogen, teratogen, suspected mutagen.

- Darkens when exposed to sulfur fumes.

Physical and Chemical Properties

- Unaffected by dilute acids and alkalis.

- Microscopically, lead-tin yellow I has very fine, slightly rounded particles with a high refractive index, while type II usually contains larger, angular particles, sometimes with conchoidal fracture.

- Lead-tin yellow I is birefracting. Lead-tin yellow II is isotropic.

- Composition = Pb2SnO4 (type I); Pb(Sn,Si)O3 (type II)

- Refractive Index = 2.29; 2.31

Resources and Citations

- H. Kuhn, "Lead-Tin Yellow", Artists Pigments, Volume 2, A. Roy (ed.), Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1993.

- E. Martin and A. Duval ‘Les deux variétés de jaune de plomb e d’étain: étude chronologique’, Studies in Conservation, 35, 1990, 117-36. Record content reviewed by EU-Artech, November 2007.

- The Dictionary of Art, Grove's Dictionaries Inc., New York, 1996 Comment: "Pigments"

- Ashok Roy, Contributed information, November 2007

- Michael McCann, Artist Beware, Watson-Guptill Publications, New York City, 1979

- R. Newman, E. Farrell, 'House Paint Pigments', Paint in America , R. Moss ed., Preservation Press, New York City, 1994

- Thomas B. Brill, Light Its Interaction with Art and Antiquities, Plenum Press, New York City, 1980

- Book and Paper Group, Paper Conservation Catalog, AIC, 1984, 1989

- Art and Architecture Thesaurus Online, https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabulary/aat/, J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles, 2000

- Pigments through the Ages http://webexhibits.org/pigments/indiv/overview/pbsnyellow.html